Preparing For An External Audit: Part One

What triggers an audit, what regulators are looking for, and regulatory remits

An external audit, or exam, as it’s commonly referred to by industry insiders, is something an investment advisor or broker-dealer is unlikely to ever look forward to. Yet external exams are a fact of life in the securities sector, and can be made less stressful and less of a voyage into the unknown with proper preparation. These next two blogs will help you prepare. Today’s blog will explore the regulators: their remits, their idiosyncrasies in approach, and how the SEC selects firms for examination. Next week’s blog will explore the exam process itself, and offer steps to help ensure your firm passes with flying colors.

WHO REGULATES WHAT

Before we go too far down the path of what goes on and what to expect in an external exam, it’s worth considering exactly what regulatory entity is responsible for what. “Most of the exams we have are with the Securities and Exchange Commission,” says Niel Armstrong, CEO and founder of Gordian Compliance Solutions, a boutique consulting firm specializing in regulatory compliance services for financial firms. “The SEC oversees registered investment advisors once they exceed $100M in assets under management. For any amount less than that, here in California at least, the state is the regulator.”

For broker-dealers the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority, or FINRA, is the primary regulator. The National Futures Association, or NFA, which regulates commodities and futures, is also a regulatory player, at least in Gordian’s world. “For us,” says Armstrong, “the big three are the SEC, the State Of California Department Of Business Oversight, and the NFA. Because we handle the compliance function for a variety of firms, each operating in its own niche, we end up working with a variety of regulators.”

So different regulators regulate different financial firms, depending on the kinds of securities they trade. No huge surprise there. But what about differences in the ways regulators operate? Are some easier to work with than others? Again, Armstrong: “FINRA is more rules based, while the SEC is more concept based. In the end, they’re both doing essentially the same thing: looking at and evaluating a lot of the same activity. But they’re going about it in markedly different ways.” This makes the regulator itself a consideration in the exam process.

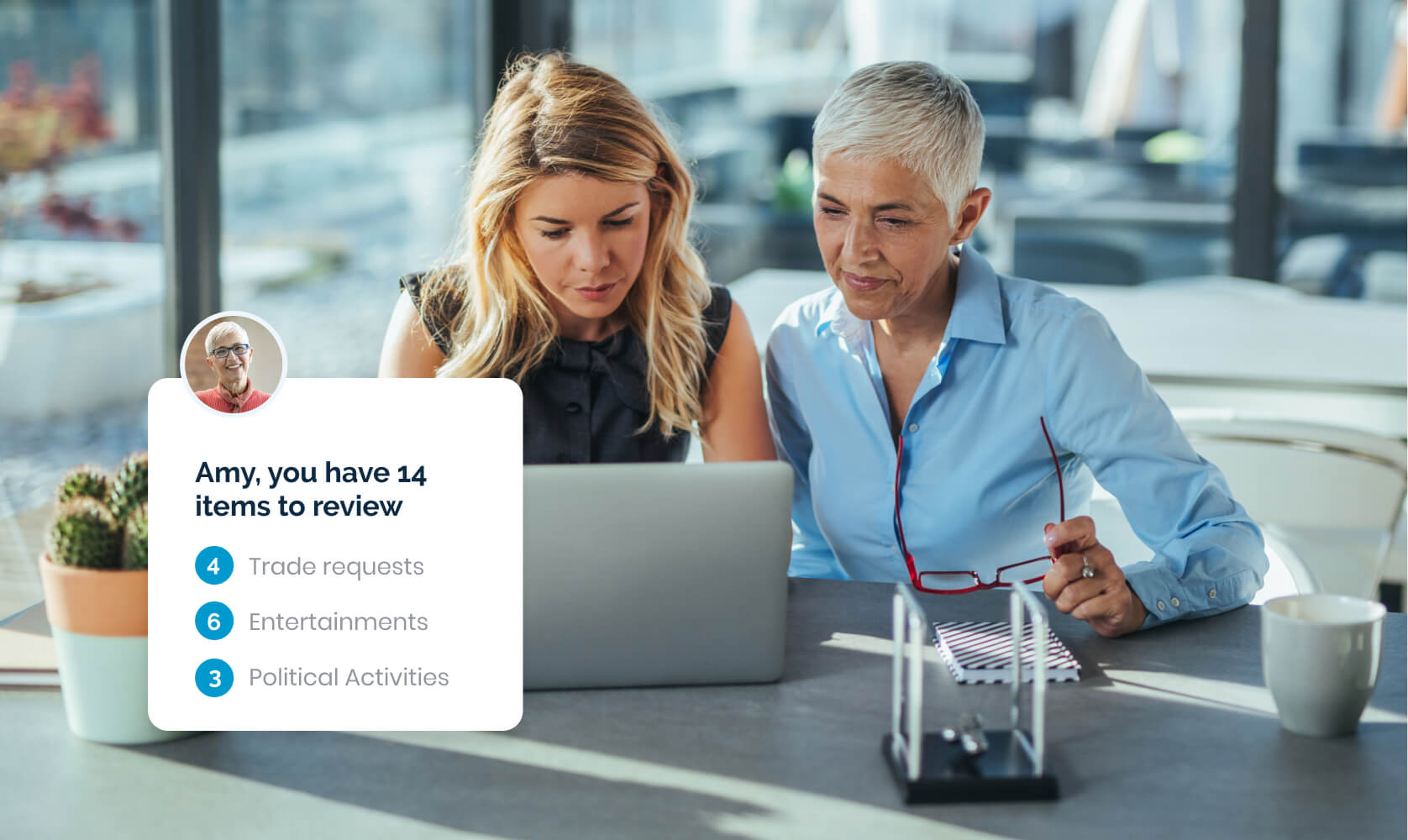

The Compliance Officer’s Guide To Employee Compliance

WHAT REGULATORS WANT

When regulators conduct an exam, if it’s just a standard exam, they’re primarily interested in two things: the firm’s code of ethics and the firm’s policies and procedures manual. The code of ethics lays out exactly what employees can and can’t do when it comes to activity that might result in a conflict of interest, things like personal trading, outside business activities, and private investments. Then the policies and procedures manual tells examiners whether or not the firm has the processes in place to enforce the code of ethics. “It’s the interaction of these two elements that will determine if the firm is in regulatory compliance,” says Armstrong, “and how well the firm will ultimately fare in the exam.”

As an example, one aspect of a code of ethics might be precisely how employees are allowed to trade their own accounts, outside of the firm. This is where good recordkeeping comes in. Regulators will be looking for evidence of supervision, and that means documentation evidencing that supervision. Again, Armstrong: “They’ll ask, what is your code of ethics? Do you require employees to disclose their outside brokerage accounts? If so, how do you review that trading activity? They’re going to want to see the outside brokerage account disclosures from all the employees.”

Automation may not be the answer to every compliance problem, but it is to this one. Good compliance software will collect, organize, and store everything that comes through it. Since said software will also be integration friendly—ready to take feeds from existing firm systems, like HR and order-management systems—even more information will be at hand, all efficiently centralized. So when regulators do ask to see your brokerage account disclosures, and evidence that someone in a supervisory capacity has reviewed them, everything can be produced quickly, easily, and definitively.

HOW FIRMS ARE NOTIFIED

As far as the SEC goes, notification of exam will come in the form of something called a document request letter. This is the formal notification that an exam is forthcoming, and will be sent to the CCO by mail. The document request letter is a request for information, typically 20 pages worth. From that point, the firm has approximately two weeks before the SEC arrives onsite. Not very much time to prepare. “These exams aren’t done on a regular schedule,” says Armstrong. “They pop up unexpectedly.”

To select firms for these exams, the SEC uses an algorithm, which looks at firms on a risk matrix: analyzing things like types of business activity, firm size, and how long it’s been since the last exam. “Some firms will go three years without an exam,” says Armstrong. “Some eight. And then suddenly the SEC sends them a document request letter.” From there, getting the SEC the documentation they want as quickly as possible is paramount: to show that you’re organized and demonstrate you’re not scrambling to cover anything up. Again, Armstrong: “Having organized records is really important from this perspective. And having them in one place, ready to go, in electronic format, is invaluable.”

Check back next week for part two of our blog series, as we explore the step-by-step of what to expect in an external exam and how best to prepare.