Understanding SEC Rule 206(4)-5: Pay-to-Play Compliance and Consequences

The Advisers Act Rule 206(4)-5 isn’t breaking news, but it is serious enough to warrant a refresher. Here, we’ll review what Rule 206(4)-5 is, why it matters, and how you can ensure your own compliance.

What is the Pay-to-Play Rule? [SEC Rule 206(4)-5]

The phrase “pay-to-play” gets around. It appears in fields as varied as sports, business, engineering, and even online gaming. Pay-to-play’s most famous cultural touchpoint may be the Payola scandals of yore, with music executives literally paying disc jockeys to play certain records. However the phrase is used, the implications are never good, which brings us to pay-to-play employed in reference to finance.

The Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) issued a rule in 2010 to address the problem of individuals or firms contributing money to candidates or office holders in the hopes of being awarded advisory business for public pension plans and other government investment accounts.

Rather than ban political donations outright from investment advisors (hardly imaginable in our age of big-money-politics) the Advisers Act Rule 206(4)-5—also known as the Pay-to-Play Rule—instead imposes a time-out. Investment advisors and covered associates can contribute what they like to a candidate or office holder but need to wait a specified amount of time before they can advise (for compensation) a government investment client related to that candidate or office holder.

A Brief History of SEC Rule 206(4)-5

Music executives didn’t invent pay-to-play. The idea of influencing those in positions of power for personal gain has a long, rich history that spans numerous fields of endeavor. Wherever it appears, pay-to-play essentially threatens the fundamental pact between advisor and investor.

The SEC saw this as a threat as far back as the 1930s, commissioning a study of investment trusts and investment companies in the wake of the 1929 stock market crash. The report generated from the study eventually compelled Congress to pass the Investment Advisers Act of 1940, which included the language: “It is hereby found that investment advisers are of national concern …”

The act was the first time the federal government formally recognized the importance of investment advice and codified it into law. It became the regulatory basis for what the SEC does to this day. The 2010 Rule 206(4)-5 piggybacks on this seminal 1940 act and specifically addresses the issue of political donations and their potentially destructive knock-on effects for investors and markets.

Who is Affected by SEC Rule 206(4)-5?

Advisers Act Rule 206(4)-5 applies to SEC-registered investment advisors or covered associates who provide investment advisory services or are seeking to provide investment advisory services to government entities.

For the SEC, a covered associate includes:

- any firm partner, managing member, or individual with a similar status or function

- any employee who solicits a government entity for the advisor

- any political action committee, or PAC, controlled by the adviser or a covered associate

Rule 206(4)-5 also applies to certain advisers exempt from registration with the SEC due to their reliance on the private adviser exemption provided by Section 203(b)(3) of the Investment Advisers Act of 1940.

Ultimately, an individual’s activities, rather than title, will determine whether the SEC considers that individual a covered associate.

Pay-To-Play Mitigation In 3 Easy Steps

Pay-to-Play Rule Requirements

In simplest overall terms, Rule 206(4)-5 restricts advisors, firm executives, or firm employees from:

- Advising a government entity for two years after they make a contribution to an elected official or candidate for office if that person has or might potentially have influence in the selection of investment advice for the related government entity.

- Paying or agreeing to pay a third-party placement agent, or finder, to solicit business from a government entity on the advisor’s behalf. This is unless the third party is a registered broker-dealer or SEC-registered investment advisor and therefore subject to the pay-to-play restriction.

- Soliciting or coordinating contributions, also known as bundling, from others to a political official, candidate, or political party in a state or locality where the advisor provides or is seeking to provide advisory services.

The SEC also makes it clear that any advisors, firm executives, or firm employees who do anything indirectly, which—if done directly—would break Rule 206(4)-5, they have still broken Rule 206(4)-5. As an example of this catch-all provision, an advisor couldn’t funnel contributions through associates such as lawyers, a spouse, or family members.

The following are deeper-dive Rule 206(4)-5 considerations:

- If an advisor already engaged with a government client makes a Rule 206(4)-5 triggering contribution, that person or firm may be obligated, in accordance with its fiduciary duties, to continue providing advisory services for a reasonable period of time during the time-out: this to allow the client to make other advisory arrangements. These interim services would go unpaid.

- Rule 206(4)-5 doesn’t specify the triggering type of officials or candidates. The scope of authority regarding whether an official can ultimately influence the selection of an investment advisor is the determining factor. In other words, Rule 206(4)-5 is vague on this point and likely purposefully so; it gives the SEC room to maneuver when assessing a potential violation.

- Contributions are also broadly defined. They could be gifts, loans, advances, or anything of value made for the purpose of influencing a federal, state, or local election. This includes payments of campaign debts, as well as transition or inaugural expenses. Contributions do not include an individual’s donated time. Donations to PACs are not automatic triggers so long as the contributions can’t be directly connected to a particular candidate.

- De minimis (small) contributions are exempt from the two-year time-out. Contributions of $350 or less per election, per covered associate for any election in which that covered associate is entitled to vote, are excepted. Contributions of $150 or less per election, per covered associate for any election in which the covered associate is not entitled to vote, are also considered de minimis.

- Rule 206(4)-5 has a look-back provision, meaning advisors must determine if a contribution was made by a covered associate two years prior to the date he or she became a covered associate. This provision applies even in the context of a merger with or acquisition of an advisor.

- Rule 206(4)-5 requires an advisor to a government entity to keep records related to contributions made to officials and candidates and of payments made to state or local political parties or PACs. Advisors with government clients must keep a list of the government entities to which they have provided advisory services in the past five years.

The Risks of Pay-to-Play

Pay-to-play is a form of corruption, and seemingly little things can add up over time to become big things. Rule 206(4)-5 takes the issue on in a fairly nuanced manner, though that approach is driven perhaps by practicality as much as anything else.

Pay-to-play can mean a state or municipality choosing an advisor with poor asset-management performance or higher fees, all because an office holder or candidate for office received a timely donation. That’s bad news for individual investors, the ones at the bottom of the pile, who depend on 401K or pension performance for their retirements.

Pay-to-play can also contribute to loss of investor confidence in the markets. That is, the more people think their investment assets aren’t being managed honestly, the less likely they are to want to sock away their precious earnings into them.

Recent SEC Rule 206(4)-5 enforcement examples

- In September of 2022, the SEC charged four investment advisory firms with violating the Pay-to-Play Rule: Asset Management Group of Bank of Hawaii, Canaan Management, LLC, Highland Capital Partners LLC, and StarVest Management, Inc. Associates from each firm had made political contributions to influential officials or candidates, after which they continued receiving advisory fees from government entities. Without admitting or denying the findings, the firms consented to a cease-and-desist order, censure, and civil penalties reflecting the specific circumstances and severity of their violations: $95,000 each for Canaan Management and Highland Capital Partners, $70,000 for StarVest Management, and $45,000 for Asset Management Group of Bank of Hawaii.

- In April of 2024, the SEC charged Wayzata Investment Partners LLC with willfully violating the Pay-to-Play Rule. The firm had provided advisory services to a government entity after an associate made a political contribution to an official with influence over adviser selection. This action violated the rule’s two-year prohibition on receiving compensation following such contributions. Without admitting or denying the SEC’s findings, the firm agreed to a cease-and-desist order, censure, and a $60,000 civil penalty. Compared to other cases, this is considered a mid-range fine, reflecting the firm’s cooperation with the investigation.

- In August of 2024, the SEC found that Obra Capital Management, LLC had violated the Pay-to-Play Rule by continuing to provide investment advisory services to a government entity within two years following a campaign contribution by one of its associates to an influential candidate. Despite agreeing to a cease-and-desist order and censure, the firm still had to pay a hefty $95,000 civil penalty.

Commissioner Peirce’s comments on the rule

Hester M. Peirce, a Republican Commissioner of the SEC, minces no words when it comes to her thoughts on the Pay-to-Play Rule. In multiple statements since her appointment, she has expressed significant concerns about the effectiveness and impact of the rule, arguing that its broad application is overly restrictive and hampers legitimate political participation by civilians.

In a September 2022 statement, Peirce described the Pay-to-Play Rule as an “exceedingly blunt instrument” that does not adequately address the nuances of political contributions and adviser-client relationships. She pointed out that enforcement actions often involve minor contributions and established advisory relationships, noting that “the Rule simply does not concern itself with whether the official would or could have prevented the adviser from playing without first paying.”

Pierce also highlighted the rule’s punitive nature and overall effect on the larger political process, explaining that it forces individuals working in investment advisory roles to forgo their right to support their preferred candidates. “A rule that penalizes people already subject to fiduciary obligations who donate money without any intent to do anything other than express their political preferences does not improve the political process,” she argued.

Peirce further noted that the Commission’s order in the Wayzata Investment Partners case, in particular, did not establish any direct link between a campaign contribution and investment decisions and therefore such charges could potentially be unfounded. She called for a more effective approach to preventing public corruption, one that does not stifle political engagement, suggesting that the SEC stay out of cases that other government bodies specifically exist to pursue.

How to Comply with Rule 206(4)-5

In the long run, regulations like Rule 206(4)-5 are beneficial to all market participants. Here’s how you can ensure your firm’s Pay-to-Play Rule and overall SEC compliance:

Align your policies: Your firms policies will serve as the guardrails against violating Rule 206(4)-5. Establish clear, strict policies that go one step above the terms of the law to minimize risk and ensure maximum compliance.

Stay educated: Make sure that you, your employees, and your associates understand Rule 206(4)-5 as it pertains to your firm or dealings. No one is exempt, so all parties need to be aware of the requirements, compliance protocol, and penalties for noncompliance. Since SEC rules are applied by federal entities, you also need to be familiar with state and local rules.

Invest in the right tools: Knowledge is power, but it takes a little more than know-how to guarantee compliance across the board. Today’s leading compliance software solutions automate the process end-to-end, taking the manual burden off employees and minimizing human error.

Test, test, test: That said, automated compliance software is not a set-it-and-forget-it solution. Conducting regular reviews of political contribution databases to check for employee names will help you verify your firm’s compliance.

While Rule 206(4)-5 is complex, it’s not insurmountably so. Due diligence in the form of a thorough reading and analysis of how the rule interacts with the kind of work your financial firm does—along with a compliance platform that makes spotting potential conflicts of interest as easy and automatic as possible—will keep your firm operating at the highest level of integrity.

Play By the Rules With StarCompliance

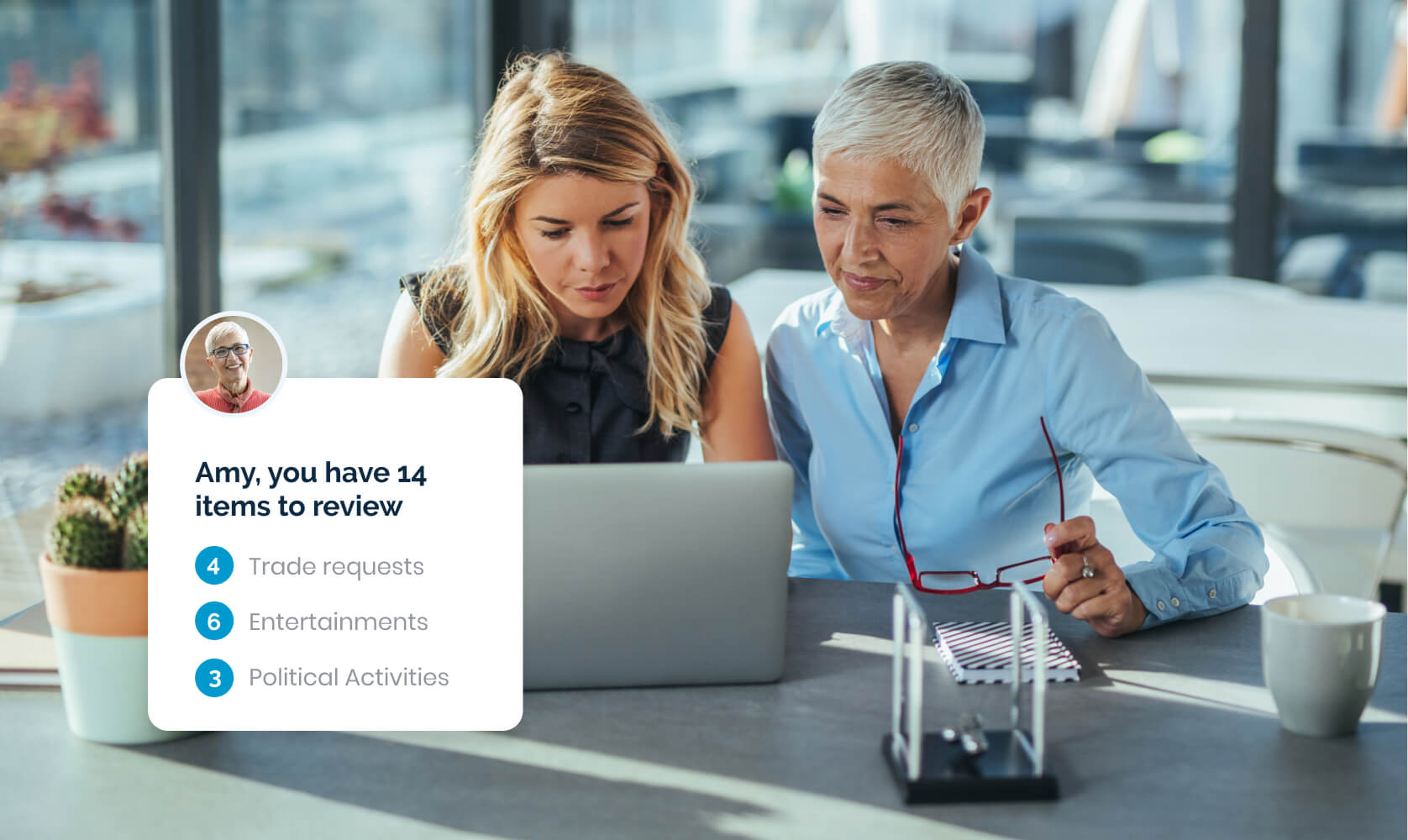

StarCompliance can help your enterprise financial firm successfully navigate the winding regulatory landscape of Rule 206(4)-5 with its Political Donations product.

As the name suggests, Political Donations addresses just the sort of thing the SEC is trying to get at with Rule 206(4)-5, at the heart of which is the notion of pre-clearance. Before covered associates make any kind of political contribution, they can log in to the STAR Platform, fill out a pre-clearance request form, and wait for an automated approval or denial decision.

With Political Donations, your firm’s code of conduct is programmed into your version of the STAR Platform, allowing you to set donation thresholds your company has established and follow precise rules to automatically check political contributions.

This automation reduces the time and effort required to track the political contributions of employees in different countries, lines of business, and offices. You can create custom profiles for employees and apply donation limits specific to, as well as across, user groups.

Political Donations also lets you produce customized reports of current and historical trends. And because the STAR Platform collects and integrates data from systems across your business—which are cross-referenced when any employee seeks permission for political activities or donations—your compliance team can more easily pinpoint high-risk employees and automatically raise cases that may violate company principles or client interests.

See the Star Political Donations product in action in this short video.

To learn more about how the STAR Platform can play its part in this important process, book a FREE demo today.

Pay-To-Play Mitigation In 3 Easy Steps