The Long Awaited Return Of South Africa

There’s real hope the continent’s shining star is regaining its shimmer

Since apartheid was formally dismantled in the early 1990’s, South Africa has been the continent’s shining star. Under 15 years of African National Congress leadership, the country had strong, stable democratic government and a prosperous, modern economy. South Africa was rightfully viewed as a good country to do business with and in. That shimmer began to fade, however, under the presidency of Jacob Zuma.

Zuma was elected in 2009. Since then the value of the rand has fallen. Unemployment is up by almost 2.0%. GDP growth is down. The budget is running a 4.0% deficit. The country’s sovereign-bond rating was downgraded to junk status last year. Inequality is at a dangerous level, with 90.0% of the wealth owned by 10.0% of the population. But newly elected president Cyril Ramaphosa has promised “a new dawn” for the country, to tackle corruption, and to “get South Africa moving.”

President Zupta

Ramaphosa has taken notable first steps in this direction, but it’s worth considering where South Africa is right now. So-called state capture , the term used to describe the level of corruption under Zuma, goes far beyond a payoff here and a private-jet flight there to secure a government contract. State capture is systemic. It’s the wholesale takeover of a government by private interests, turning the apparatus of the state into a personal profit-taking machine.

The person or persons directing and benefitting from state capture are referred to as oligarchs. In South Africa the oligarchs were the Gupta family (they have reportedly fled the country since Ramaphosa’s election). One estimate puts the Guptas’ profit from state capture at $2 billion. They had a compound in Johannesburg that rivaled the South African state’s executive compound, and regularly summoned ministers there from the highest levels of government.

Cyril ramifications

Cyril Ramaphosa is a miner turned union boss turned wealthy businessman. Ramaphosa edged out Zuma’s ex-wife, Nkosazana Dlamini-Zuma, in last December’s ANC election for party leader. Some of his important first acts as president have been to replace key cabinet ministers, perceived as either too close to Zuma, tied in with the Guptas, ineffective at their jobs, or all of the above. Nhlanhla Nene is back as finance minister. Nene was finance minister under Zuma until he was abruptly fired for not going along with Zuma on frivolous state-funded projects.

Pravin Gordhan is back, as well. Seen as market friendly, Gordhan was also fired by Zuma as finance minister. Gordhan will be overseeing South Africa’s massive state-owned companies, viewed as another center of state capture. Most recently, Ramaphosa replaced Tom Moyane as commissioner of the South African Revenue Service, the country’s tax authority. Tax revenues declined noticeably under Moyane, and critics claimed he too was at the beck and call of the Guptas.

The times they are a changin’

It was a long time coming, but South Africa’s Financial Sector Regulation Act, or FSRA, has just gone into effect. Or at least a portion of it has. On April 1 the Prudential Authority was officially on the job regulating South Africa’s financial sector. The Prudential Authority, or PA, is part one of a two-part regulatory model the FSRA will eventually put into place: so-called “Twin Peaks.”

The PA is officially part of the South African Reserve Bank, or SARB, and consists of four sections:

- Financial Conglomerate Supervision Department.

- Banking, Insurance, and Financial Market Infrastructure Supervision Department.

- Risk Support Department.

- Policy, Statistics, and Industry Support Department.

Part two of Twin Peaks will be a market-conduct regulator, which will exist separately from the SARB and the PA. This regulator will be known as the Financial Sector Conduct Authority. An inaugural date for its coming into being is presumably forthcoming, but there’s no official word yet. The irony in all this is, the FSRA was initiated under Jacob Zuma in 2011 and signed into law by him last August.

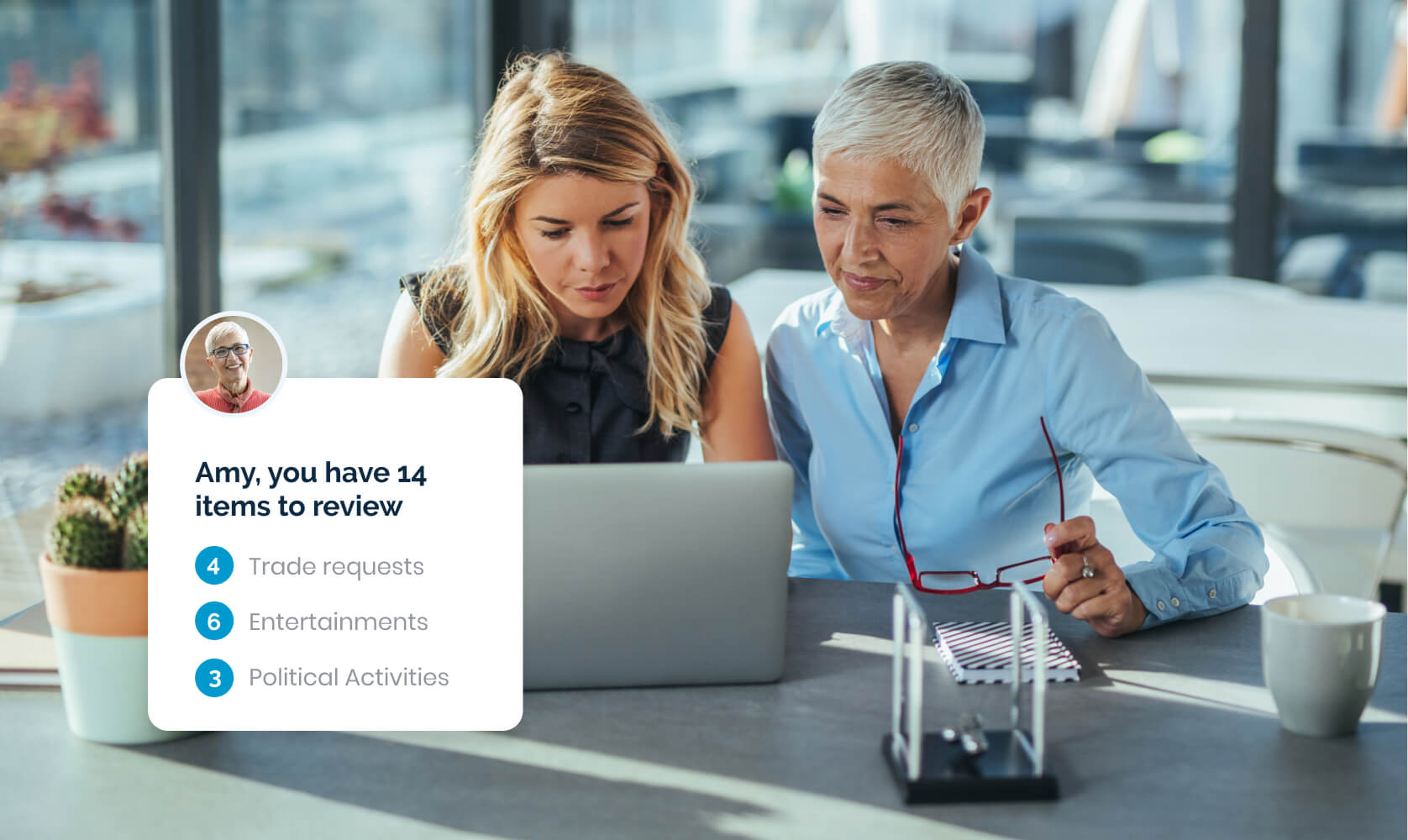

It’s worth noting this Twin Peaks model of financial regulation is used in other countries, which bodes well for its effectiveness in South Africa. But the FSRA’s mere imminent existence should signal financial institutions that it’s time to step up their compliance programs and establish more efficient ways of monitoring employee conflicts of interest and market abuse. Firms could potentially demonstrate their commitment to the new regulatory regime by having a modern compliance system in place.

There is a light

Back in the new president’s camp, more cabinet changes are believed to be coming. But Ramaphosa has to be careful trying to balance the change necessary for the country to flourish again with the split in the ANC. Ramaphosa himself served Zuma as deputy leader of the party for several years. That’s a little close for comfort for some observers. Still, with the resignation of Zuma, the ascendancy of Ramaphosa, and the FSRA coming into full effect, the shimmer is slowly but surely returning to Africa’s shining star.