GDPR PART 1: Big Data, Big Update

A primer on the looming General Data Protection Regulation: What it is and how it came about

Visit the General Data Protection Regulation website, and you can’t miss the countdown clock. Prominently displayed above the fold, it counts not just the days left until enforcement officially begins, but also the hours, minutes, and seconds. Yes, seconds.

This level of detail can perhaps be taken as a metaphor for the level of detail the European Union has written into its expansive new data-privacy regulation. This level of prominence, and the fact there’s a countdown clock at all, certainly underlines the seriousness with which the EU expects those entities that will be affected by the rule to take it.

However you interpret the marketing tactics, there should be little doubt the EU means business when it comes to the looming General Data Protection Regulation, or GDPR. There should also be little doubt about the impact in store for any enterprise or financial institution planning to do business with EU citizens after May 25, 2018, no matter where in the world they’re headquartered or where they do their work.

The following is the first in a two-part blog series exploring precisely how the GDPR came about and exactly what that impact will be.

Out with the old

At it’s most basic, the GDPR is a new set of EU data-privacy rules, written to supersede the current data-privacy regime: Data Protection Directive 95/46/EC, or DPD.

The DPD was enacted 22 years ago, in 1995. That’s ancient times from our Big Data vantage point. It’s a data-driven world now, to a degree almost unimaginable two decades ago. And not just in terms of the amount of data now traded between individuals, corporations, and governments, but also in how easily it’s traded. So much of the digital world is now connected, or has the potential to be.

Given all this, it wasn’t unreasonable for the EU to think it was time for a regulatory revisit. The GDPR was debated in the EU Parliament for four years and formally approved in April 2016, with a two-year enforcement lag to give those affected by it time to prepare. Officially, it’s designed to “harmonize data-privacy laws across Europe, to protect and empower all EU citizens’ data privacy, and to reshape the way organizations across the region approach data privacy.”

Data privacy is clearly the operative phrase here, and conveys a lot all on its own about how the EU views the relationship of data to its citizens.

This time it’s personal

Whether you’re talking about the GDPR or the DPD, for the EU it’s all about data privacy. In particular, the data privacy of the data subject. Now there’s a term—data subject—that almost certainly wasn’t around in 1995. A data subject, as used in the UK’s Data Protection Act is “an individual who is the subject of personal data.” In 2017, that’s pretty much anyone on the planet who uses a smartphone, tablet, or computer. In a highly developed region like the EU, it’s pretty much everyone.

Data controller and data processor are two more important data-related terms to get your head around. The data controller, as defined in the DPD, is “the natural or legal person, public authority, agency or any other body which alone or jointly with others determines the purposes and means of the processing of personal data.” The data processor is “the natural or legal person, public authority, agency or any other body which processes personal data on behalf of the controller.”

For example, Chase Bank might be a customer’s data controller, while Amazon Web Services, providing cloud services to Chase, would be that customer’s data processor.

From nothing, something

The EU traces its heritage of data-subjects’ data-privacy rights all the way back to 1980, when the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, or OECD, published its Guidelines on the Protection of Privacy and Transborder Flows of Personal Data. This is well before the age of serious electronic data, but data has always gotten around in one form or another. What’s notable is, even as far back as the 80’s the idea of data privacy had taken hold somewhere in the collective, and regulatory, consciousness.

The eight principles enumerated in the OECD Guidelines “set out to protect personal data and the fundamental human right of privacy.” They are:

- Collection Limitation Principle—There should be limits to the collection of personal data, which should obtained with the consent of the data subject.

- Data Quality Principle—Personal data should be relevant to the specific purpose for which it was collected.

- Purpose Specification Principle—The purpose for the collection of data should be specified at the time of collection.

- Use Limitation Principle—Personal data should only be used for the purpose it was originally intended for.

- Security Safeguards Principle—Personal data should be protected against risks such as loss, destruction, modification, or unauthorized access.

- Openness Principle—Individuals should have easy access to information about their personal data, such as who’s holding it and what it’s being used for.

- Individual Participation Principle—An individual should have the right to know if a controller has data about him or her and to have free access to that data.

- Accountability Principle—Data controllers should be accountable for complying with all the data-rights measures previously detailed.

There are lots of “shoulds” in this manifesto but no “musts.” That’s because these were just guidelines—core principles nations would ideally draw upon to try and make actual laws with. And from this highly specific, if non-binding, philosophical underpinning, the EU did just that to create the DPD.

The DPD was the first attempt to harmonize data-privacy laws across member states, and did create what are known as Data Protection Authorities, or DPAs. There’s a DPA in each member state, whose job is to “supervise the application of [the DPD] and serve as the regulatory body for interactions with businesses and citizens.” But for all its ambitions, the DPD is still only a directive, i.e., member states have room to maneuver when it comes to turning its particulars into law.

A Bill of Data Rights

Depending on your point of view, the GDPR fixes this issue of member-state maneuvering room. As an EU regulation, the GDPR will go into effect as law in every member state on May 25. Period. Building on the foundation laid in the DPD, which used the privacy principles set out in the OECD’s Guidelines, the GDPR sets forth its own Big Data-age bill of data rights:

- Breach Notification—Mandatory in all member states where a breach is likely to result in a risk for the rights and freedoms of individuals.

- Right to Access—Data subjects have the right to know whether or not personal data concerning them is being processed, by what entity, and for what purpose.

- Right to be Forgotten—Also known as Data Erasure, this entitles the data subject to have his or her personal data erased and further dissemination ceased.

- Data Portability—Data subjects have the right to receive their personal data in a commonly used, electronic format and to transmit that data to another controller.

- Privacy by Design—Calls for the inclusion of data protection from the onset of the design of data systems, rather than as a bolted-on afterthought.

We the peoples

For the EU, data privacy is fundamental. A human right, like any other. And like others, it’s typically up to the state to guarantee it. Or in this case, a union of states. A far bigger and ambitious piece of legislation than the DPD, the GDPR will do just that, beginning May 25. In case you’re wondering, that’s currently 120 days, 12 hours, 47 minutes, and 56 seconds away. But who’s counting?

Ready to learn in detail how the GDPR will affect your enterprise or financial institution moving forward, and what you need to do to prepare? Read part two in our blog series about the fast-approaching GDPR here.

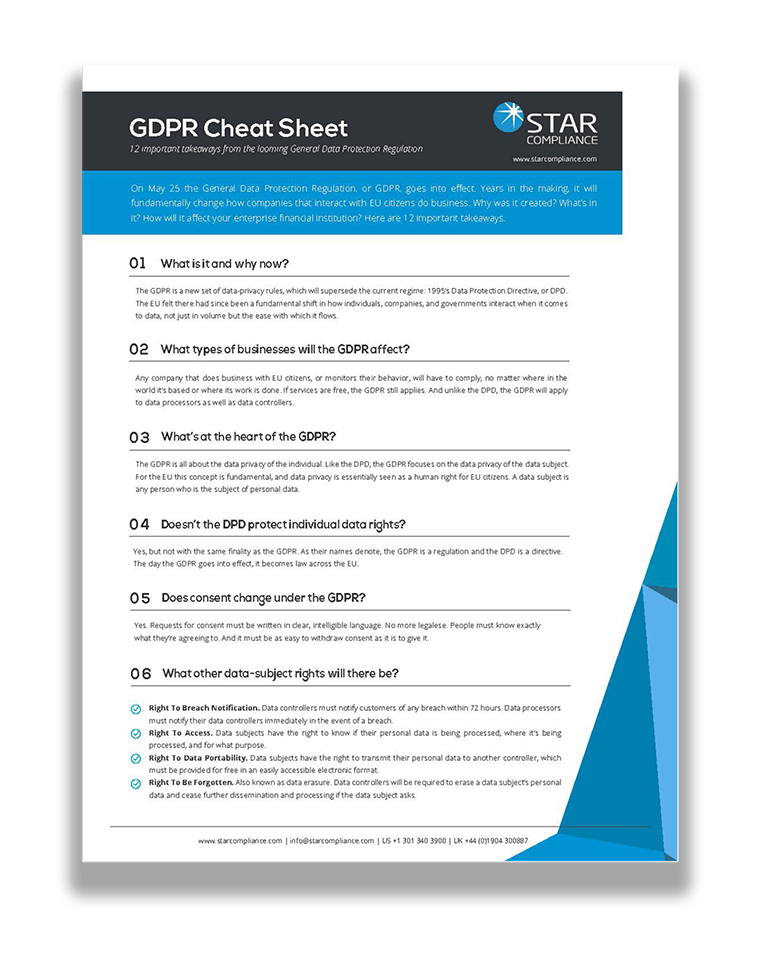

GDPR Cheat Sheet